Introduction

The word “taboo” comes from Polynesian languages—tapu or tabu—meaning “set apart” or “forbidden.” Across cultures, taboos mark boundaries around what is considered pure or impure, polite or offensive, sacred or profane. To outsiders, taboos can seem bizarre: no shoes indoors, no whistling at night, avoiding certain numbers, refusing certain foods, or shunning particular gestures. Yet within their cultural context, these prohibitions often serve vital functions.

Taboos are not just lists of “don’ts.” They are social technologies—shared understandings that help communities manage risk, maintain identity, show respect, and organize daily life. They evolve, fade, and sometimes reappear in new forms. What follows is a guided tour of taboos that may look unusual from the outside, alongside the reasons they persist.

What Exactly Is a Taboo?

A taboo is a rule against a behavior, object, or idea that a group considers off-limits. The force of taboos varies: some are merely frowned upon, others are deeply sacred or tied to legal penalties. Anthropologists such as Mary Douglas (in “Purity and Danger”) and Marvin Harris have shown that taboos often:

- Protect health and resources (e.g., food safety, environmental conservation).

- Signal group identity and cohesion (who we are vs. who we are not).

- Reinforce social hierarchy and roles (who may do what, when, and where).

- Set boundaries between sacred and ordinary (ritual purity and respect).

- Reduce uncertainty, anxiety, or social conflict (clear rules in ambiguous situations).

Food and Drink Taboos

Few taboos are as visible—and as emotionally charged—as those surrounding food. What is delicacy in one place can be unthinkable in another.

Religious and Ethical Diets

- Pork and alcohol: Many Muslims avoid pork and alcohol for religious reasons. In Judaism, pork and shellfish are non-kosher, and meat and dairy are traditionally not mixed.

- Beef: Many Hindus avoid beef, with cows regarded as sacred in many traditions; practices vary across regions and individuals.

- Fasting times: Fasting or abstaining from certain foods occurs in many faiths, such as during Ramadan for Muslims, Lent for many Christians, and various fast days in Judaism and other religions.

What Counts as “Food”

- Insects: In much of Africa, Asia, and Latin America, insects are nutritious staples. In many Western societies, insect eating is taboo or squeamishness-inducing, though this is changing.

- Dogs, horses, and other animals: Cultural attitudes vary widely; what is taboo in one place may be permitted or historically customary in another. Laws and social views continue to evolve.

Everyday Etiquette

- Left hand vs. right hand: In parts of South Asia, North and East Africa, and the Middle East, eating or passing items with the left hand can be considered impolite, linked to traditional hygiene practices.

- Table manners: Slurping noodles may be perfectly polite in Japan, where it can signal that food is enjoyed, whereas it may be frowned upon elsewhere.

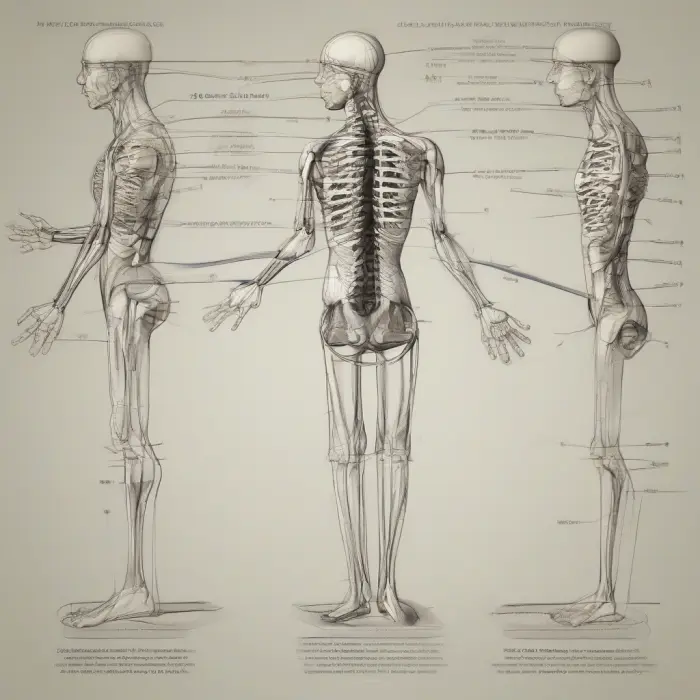

Body, Space, and Touch

The body is a cultural canvas: how we sit, stand, touch, or gesture communicates deep social meanings.

- Head and feet: In Thailand and neighboring countries, the head is considered especially respectful; touching someone’s head can be taboo. Pointing the soles of feet at people or religious images is considered disrespectful.

- Shoes indoors: Removing shoes before entering a home is common in Japan, Korea, Scandinavia, and many other places. Bringing outdoor shoes inside can be considered dirty or disrespectful.

- Public displays of affection: Acceptability varies widely. Some communities welcome affectionate greetings; others discourage or legally restrict public intimacy.

- Gestures: Hand signs can carry very different meanings across cultures. A sign that seems harmless in one place may be rude in another; orientation and context matter.

Language and Naming

Words have power. Many societies police language tightly—especially names, sacred words, and references to the dead.

- Profanity and euphemism: Swearing is a widespread linguistic taboo, often tied to religion, bodily functions, or sexuality. Euphemisms soften forbidden topics: “passed away” instead of “died,” for instance.

- Naming taboos: In imperial China, it was taboo to write or speak the personal name of the emperor, leading to altered characters in texts. In many Aboriginal Australian communities, there are protocols around using the names or images of recently deceased people.

- Honorifics and titles: Using first names, given names, or titles varies; what feels friendly to some can feel disrespectful to others who expect formal address.

Kinship, Sexuality, and Relationship Rules

Most societies have a strong incest taboo, though the exact definitions of prohibited relationships vary. Marriage customs differ widely, from exogamy (marrying outside a group) to endogamy (marrying within a group), with rules around kinship, age, and ritual status.

Views on sexuality and gender are shaped by religious, legal, and cultural norms. What one place regards as taboo another may celebrate. These norms continue to evolve, and debates around them can be especially intense because they sit at the intersection of identity, morality, and law.

Death, Mourning, and the Sacred

Death rituals are rich with taboos about what to touch, say, wear, or even think.

- Colors of mourning: Black is common in many Western contexts; white is associated with mourning in parts of East and South Asia. Red may be avoided at funerals in some traditions where it symbolizes celebration.

- Handling remains: Practices range from burial to cremation, sky burials, and other rituals. Taboos can restrict who may prepare the body and how.

- Speaking of the dead: Name avoidance customs exist in several cultures; some restrict images or recordings of the deceased for a period of mourning.

Time, Numbers, and the Unseen

Taboos often map onto calendars and numerology, shaping when activities are allowed and which numbers bring luck or misfortune.

- Tetraphobia (4): In parts of East Asia, the number four is avoided because it can sound like the word for “death” in some languages. Building floors or hospital rooms may skip the number.

- Triskaidekaphobia (13): In many Western countries, the number 13 is considered unlucky, leading to missing floors in buildings and superstitions around Friday the 13th.

- Sacred days: Rest days, sabbaths, and festival seasons carry special restrictions and permissions that shape work, travel, and social life.

Gifts and Everyday Etiquette

A thoughtful gift in one culture can unintentionally send the wrong message in another.

- Clocks as gifts: In parts of Chinese-speaking contexts, gifting a clock can be avoided due to an association with attending funerals in a homophonous phrase.

- Knives or scissors: In several cultures, sharp objects can symbolize “cutting” a relationship; if given, a token coin may be exchanged to “buy” the gift and neutralize the symbolism.

- Flowers: The number and type of flowers matter in many places; for example, even numbers or specific flowers may be reserved for funerals in certain Eastern European traditions.

- Tipping: In the United States, tipping service workers is expected; in Japan, overt tipping can be seen as awkward or impolite, with gratitude expressed differently.

Taboos and Health

Taboos often emerge from historical public health concerns and resource management. Some dietary restrictions may once have limited contamination risks; prohibitions around water sources, certain foods in heat, or hygiene practices can preserve community well-being. Over time, these rules can take on moral or spiritual dimensions that outlast their original practical purpose.

Modernity, Globalization, and Changing Taboos

Taboos are not static. Global travel, migration, and digital life can clash with local norms or create new ones:

- Digital taboos: Filming strangers, taking selfies in solemn places, or sharing private family events online can be frowned upon or restricted.

- Shifts in food culture: Sushi, once considered exotic or off-putting in many Western contexts, is now mainstream. Insect-based foods are entering markets as sustainable protein options.

- From prohibition to regulation: Alcohol, cannabis, and other controlled substances occupy shifting ground between moral taboo, social acceptance, and legal frameworks, depending on place and era.

Occasionally, taboos invert: what was once forbidden becomes fashionable, while formerly neutral practices become stigmatized. The speed of change can be disorienting, especially across generations.

Common Misunderstandings

- “Taboos are irrational.” Many taboos have practical origins or social logic. Even when their original purpose fades, they can remain important for identity and solidarity.

- “Everyone in a culture follows the same taboos.” Variation is normal. Class, age, region, religion, and personal belief matter; diasporas often adapt rules.

- “Breaking a taboo is just being bold.” Violating taboos can cause real harm or distress, especially around sacred spaces, grief, or other sensitive contexts.

A Practical Guide for Travelers and Guests

Navigating unfamiliar taboos does not require expert knowledge—just curiosity and care.

- Observe before acting: watch how locals behave in homes, temples, markets, and public spaces.

- Ask polite questions: “Is there anything I should avoid here?” is usually welcome.

- When in doubt, go modest: modest dress, quiet tones in sacred places, and conservative gestures travel well.

- Follow hosts’ cues: let your hosts lead the way with shoes, gifts, seating, and table manners.

- Accept corrections gracefully: mistakes happen; a sincere apology and quick adjustment go far.

Short Snapshots: Taboos in Context

An apartment block in Tokyo leaps from 3 to 5; an office tower in Chicago skips 13. Different histories, similar outcomes: buildings quietly rearrange numbers to soothe cultural anxieties.

In historical China, scholars reworded texts to avoid the emperor’s personal name. In several Indigenous Australian communities, name and image avoidance honors the recently deceased. Language is never just words—it is respect, memory, and community.

A neat line of footwear outside a home signals a boundary: the threshold between public dust and private sanctuary. Crossing it lightly—socks or slippers on—shows care for the shared space.

Respect and Ethics

Writing about taboos risks exoticizing other people’s lives. The aim is not to mock what seems unusual but to understand how taboos do social work: preserving dignity, managing risk, and marking the sacred. As cultures change and interact, sensitivity matters. What looks “bizarre” from the outside may be ordinary, meaningful, or protective from within.

Further Reading

- Purity and Danger by Mary Douglas

- Good to Eat (also published as The Sacred Cow and the Abominable Pig) by Marvin Harris

- Watching the English by Kate Fox

- On the origins of “taboo”: studies of Polynesian tapu in Pacific anthropology

These works offer frameworks for thinking about why taboos arise, how they operate, and how they shift across time and place.

Conclusion

Cultural taboos—whether about food, touch, speech, or time—draw the invisible lines that organize social life. They reveal what a society honors, fears, or seeks to protect. Understanding them deepens empathy, smooths cross-cultural encounters, and reminds us that our own “normal” is, in its way, just as extraordinary.