Amazing Facts About the Unique Features of Octopuses

Octopuses are among the most extraordinary animals on Earth. These eight-armed cephalopods combine alien-like anatomy with remarkable intelligence, making them masters of disguise, escape, and problem-solving. Here are the standout features that make octopuses so uniquely amazing.

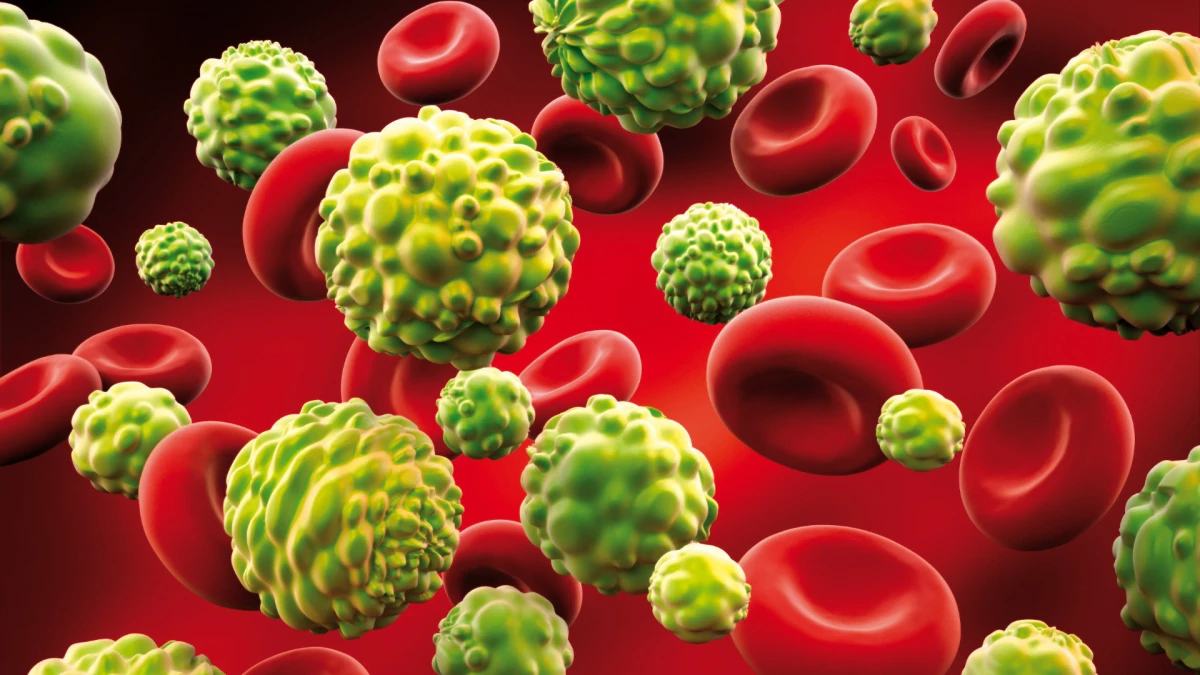

Three Hearts and Blue Blood

Octopuses have three hearts. Two “branchial” hearts pump blood through the gills, while the central “systemic” heart sends oxygenated blood to the rest of the body. Their blood is blue because it’s based on copper-rich hemocyanin, not iron-based hemoglobin. Hemocyanin is especially effective at transporting oxygen in cold, low-oxygen waters, which suits many octopus habitats.

Oddly, the systemic heart pauses during jet propulsion. That makes sustained fast swimming tiring, which is one reason octopuses often prefer to crawl or glide rather than sprint.

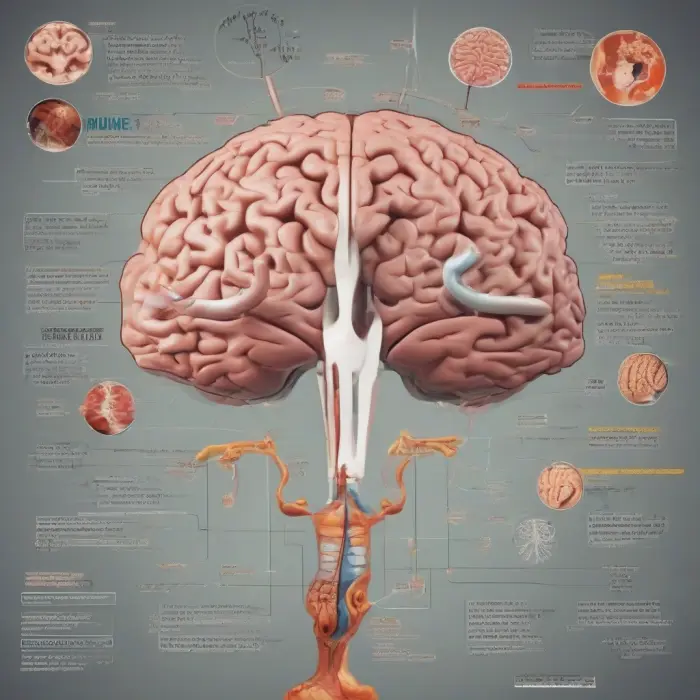

A Brain in Every Arm (Almost)

Octopuses possess a large, complex brain—comparable in neuron count to that of many mammals—and a highly unusual nervous system. Roughly two-thirds of their neurons reside in their arms, each of which contains semi-autonomous neural circuits. This allows arms to explore, grasp, and even coordinate local movements without constant oversight from the central brain.

The result: astonishing dexterity. An arm can taste, touch, and manipulate objects independently, while the animal’s central brain focuses on strategy—like opening a jar, raiding a crab trap, or planning an escape.

Masters of Camouflage (Despite Being Colorblind)

Octopuses can transform their appearance in fractions of a second using three main skin structures:

- Chromatophores: tiny pigment sacs that expand and contract to change color and contrast.

- Iridophores and leucophores: reflective and scattering cells that create iridescence and adjust brightness.

- Papillae: muscular bumps that alter skin texture to mimic sand, coral, or algae.

They likely see mainly in shades of light and dark, yet they match their surroundings with uncanny accuracy. How? Research suggests they rely on brightness, pattern, texture, polarization sensitivity, and even light-sensing proteins in the skin. The result is near-instant camouflage that can fool both predators and prey—and vivid displays for communication, such as the dramatic “passing cloud” wave of darkness sweeping across the body.

Soft-Bodied Contortionists

With no bones and only a hard beak, an octopus can squeeze through any opening just larger than its beak. Their body is a “muscular hydrostat,” using layers of muscle to change shape and stiffness on the fly—an engineering trick that has inspired a generation of soft robots.

Those miracle arms can bend anywhere, extend, twist, and conform to complex objects. It’s like having eight flexible hands with thousands of individually controllable suction cups.

Suckers That Feel and Taste

Each sucker is both a vacuum cup and a sensory organ. Packed with touch and chemoreceptors, suckers allow octopuses to “taste by touch,” detecting subtle chemical cues on rocks, shells, or prey. Remarkably, they usually avoid sticking to their own skin, thanks to a combination of neural control and self-recognition of skin chemistry.

Ink: A Smokescreen with a Sting

When threatened, many octopus species eject a cloud of ink mixed with mucus. This creates a visual smokescreen and can dull a predator’s sense of smell and taste, buying precious seconds to escape. Not all octopuses have ink sacs—some deep-sea species have lost them—so ink is a powerful but not universal defense.

Venomous by Nature

All octopuses are venomous to some degree. They deliver toxins through their saliva, often after drilling a tiny hole in a shell with their beak and rasping tongue (radula). The famous blue-ringed octopuses carry potent tetrodotoxin, which can be dangerous to humans, while most species use venom primarily to subdue crustaceans and mollusks.

Tool Use, Problem-Solving, and Personality

Octopuses are renowned problem-solvers. They navigate mazes, open screw-top jars, unclip latches, and remember solutions. Some have been observed collecting and carrying coconut shells or shells to assemble portable shelters—classic tool use.

They also show individual “personalities,” with differences in boldness, curiosity, and playfulness. In aquariums, they’re notorious escape artists; stories abound of octopuses slipping out at night to raid nearby tanks and returning before morning rounds.

Communication and Mimicry

Through rapid color changes, body posture, and movement, octopuses convey mood, intent, and camouflage. Some species even impersonate other animals: the mimic octopus can adopt the shapes and behaviors of lionfish, sea snakes, and flatfish to deter predators.

Researchers have also documented octopuses throwing shells and silt—sometimes apparently at other octopuses—suggesting a surprising social twist in a mostly solitary lifestyle.

Epic Reproduction—and a Tragic Finale

Octopuses are generally semelparous: they reproduce once, then die. Males use a specialized arm, the hectocotylus, to transfer spermatophores to the female. After laying thousands of eggs, a mother tends them meticulously, cleaning and aerating until they hatch—often without eating. The brooding period in some deep-sea species can exceed four years, one of the longest known in the animal kingdom. After hatching, the mother dies, and the tiny hatchlings begin life on their own.

Regeneration Superpowers

Lose an arm? An octopus can regrow it, complete with nerves, muscles, and function. This regeneration is not just cosmetic—it restores the arm’s sensory-motor sophistication, including thousands of new, working suckers.

From Tidepools to the Abyss

Octopuses live in nearly every ocean habitat—from shallow seagrass beds and coral reefs to the deep sea. Giant Pacific octopuses can weigh more than 50 kilograms with arm spans of several meters, while the tiny Octopus wolfi is smaller than a bottle cap. Some species build “octopus cities” by clustering dens and shell piles; others roam as solitary, stealthy hunters.

Genes That Rewrite Themselves

Cephalopods, including octopuses, are champions of RNA editing—tweaking the instructions copied from DNA before proteins are made. Many of these edits occur in nervous tissue and can change with temperature over days, potentially letting octopuses fine-tune their neural proteins to their environment. Their genomes also feature expansions of certain gene families related to neural development and signaling, aligning with their cognitive prowess.

Bipedal Walking and Unusual Gaits

Beyond jetting and crawling, some octopuses “walk” on two arms while tucking the others, sometimes disguising themselves as rolling algae or debris. This quirky gait lets them move while maintaining camouflage or keeping other arms free to hold tools or shells.

The Science of Staying Alive

Octopuses have keen eyesight and can detect polarized light, which may improve contrast in the underwater world. Balance organs called statocysts help them orient in three dimensions. Although they can sprint with jet propulsion, their heart physiology favors short bursts; most of the time they glide, crawl, and carefully plan their moves to conserve energy.

Ethics, Sentience, and Conservation

Mounting evidence suggests octopuses feel pain and have complex inner lives. This has led some countries to formally recognize cephalopods as sentient animals under welfare laws. In the wild, many species are short-lived and adaptable, but ocean warming and deoxygenation may challenge them, particularly because their copper-based blood and high oxygen demands are sensitive to temperature and oxygen levels. Debates continue about the ethics of octopus farming, given their cognitive abilities and solitary nature.