This is what could happen to a child who doesn’t get vaccinated

Public radio outlets like NPR have chronicled, time and again, how quickly once-rare infections return when vaccination rates slip. Here is the bigger picture—what can happen to an unvaccinated child, how outbreaks ripple through families and communities, and how vaccines change the story.

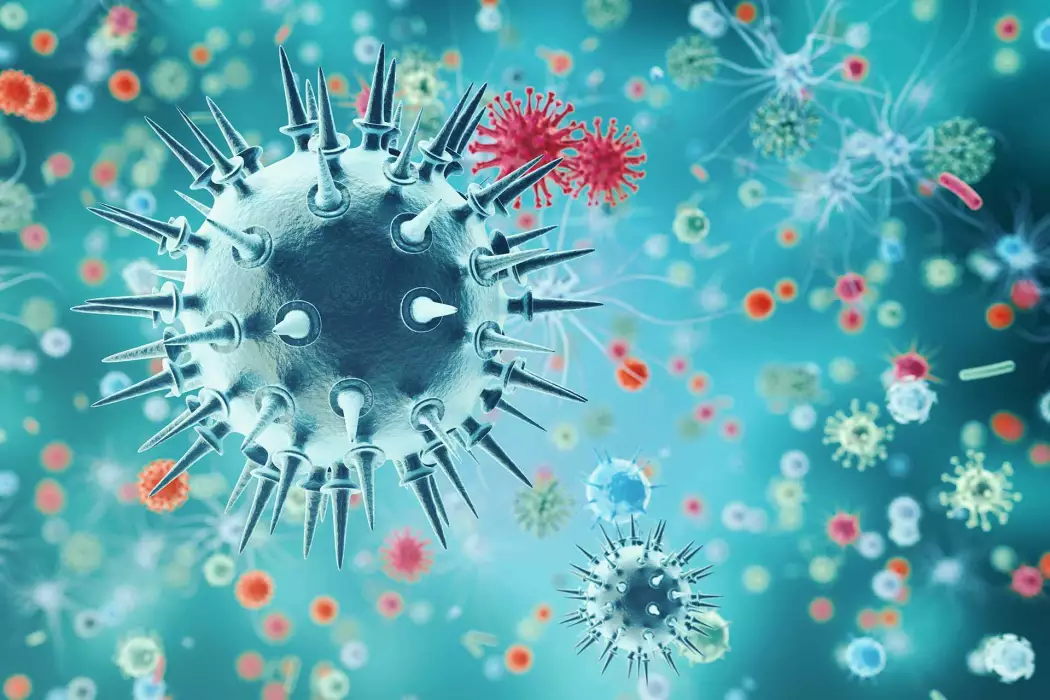

How infections find unvaccinated children

Contagious viruses and bacteria never entirely disappear. They circulate locally, travel with people, and look for gaps in immunity. When a child is not vaccinated, several things stack the odds against them:

- Higher exposure risk in everyday places: schools, daycares, sports, houses of worship, public transit, and clinics.

- Travel and visitors: a single traveler can reintroduce measles or pertussis into a community with lower vaccination coverage.

- Household dynamics: infants too young for full vaccination and immunocompromised family members rely on others’ immunity for protection.

Diseases with very high contagiousness—like measles, which can linger in the air for up to two hours—exploit even small drops in community vaccination. That’s why public health experts stress maintaining very high coverage, especially for diseases with a high basic reproduction number.

What could happen to an unvaccinated child

Outcomes vary by disease, age, and health status. Most vaccine-preventable infections start like a cold or a stomach bug—then can turn serious quickly.

Measles

Starts with fever, cough, runny nose, and red eyes, followed by a rash. Complications can include:

- Pneumonia, the most common cause of measles-related death in children.

- Dehydration requiring IV fluids and hospitalization.

- Encephalitis (brain swelling) that can cause seizures, deafness, or developmental regression.

- SSPE, a rare but fatal brain disorder that appears years later after apparent recovery.

In recent U.S. outbreaks, roughly 1 in 5 unvaccinated people with measles have been hospitalized; in low-resource settings, the risks are higher.

Pertussis (whooping cough)

Begins like a cold, then progresses to violent coughing fits; young infants may stop breathing briefly. Complications can include pneumonia, seizures, brain injury, and death, especially in babies under 6 months. About half of infected infants may require hospital care.

Polio

Most infections are silent, but a small percentage leads to meningitis or acute flaccid paralysis. Among those with paralysis, some have permanent disability, and a subset die when breathing muscles are affected. Post-polio syndrome can emerge decades later.

Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) and pneumococcal disease

These bacteria can cause invasive infections like meningitis, bloodstream infection, and epiglottitis. Even with treatment, there is risk of death or long-term complications such as hearing loss or developmental delays.

Varicella (chickenpox)

Often mild, but before vaccination it caused thousands of hospitalizations annually in the U.S. Complications include bacterial skin infections, pneumonia, cerebellar ataxia, and, rarely, life-threatening invasive infections.

Rotavirus

Causes vomiting and severe diarrhea. The greatest danger is dehydration, which can escalate quickly in young children and require emergency care or hospitalization.

Influenza (the flu)

Seasonal flu can be unpredictable. Children—especially those under 5 or with chronic conditions—face higher risks of pneumonia, dehydration, ear and sinus infections, and, in severe cases, encephalopathy or death. Many pediatric flu deaths occur in previously healthy children.

Meningococcal disease

Rare but rapidly progressive. Can cause meningitis or sepsis, with symptoms worsening over hours. Even with treatment, 10–15% die; 10–20% of survivors have serious long-term effects such as limb loss or neurological impairment.

Hepatitis B

Infants and young children who become infected are much more likely to develop chronic infection, which can lead later in life to cirrhosis or liver cancer.

Rubella

Usually mild in children, but if an unvaccinated child transmits rubella to a pregnant person, the fetus is at risk of congenital rubella syndrome—causing heart defects, cataracts, deafness, and developmental disability.

Beyond illness: the cascading effects on family and community

- School and childcare exclusion: during outbreaks, unvaccinated children are typically excluded for the disease’s incubation period (often 2–3 weeks for measles), disrupting learning and caregivers’ work.

- Quarantine and contact tracing: families may face repeated quarantines if exposures recur.

- Medical bills and travel constraints: emergency visits, hospitalization, and follow-up care add financial and emotional strain; some destinations or programs require proof of vaccination.

- Risk to vulnerable people: infants, cancer patients, transplant recipients, and others who cannot be fully vaccinated depend on high community coverage for protection.

Why vaccines change the story

Vaccines train the immune system to recognize threats before they cause severe disease. They are tested in large clinical trials, continuously monitored in real-world systems, and updated when needed. Typical side effects are short-lived—soreness, fever, tiredness. Serious adverse events are very rare, and for nearly all children the benefits of vaccination far outweigh the risks of disease.

Decades of high-quality research have found no link between vaccines and autism. The small 1998 paper that fueled this myth was retracted for serious misconduct, and numerous large studies since have shown no association.

Community benefit matters, too. When enough people are vaccinated, chains of transmission are broken—a shield often called “herd immunity.” For extremely contagious infections like measles, about 95% coverage is needed to prevent spread.

Common questions and concerns

Is natural immunity better?

Infection can confer immunity, but at a steep cost: the risks of hospitalization, disability, or death. Vaccines provide targeted training with far fewer risks.

What if my child is behind?

There are CDC-endorsed catch-up schedules that safely and efficiently protect children who start late. Your pediatrician or local health department can help build a plan.

What about ingredients?

Vaccine components are present in tiny, carefully studied amounts. Preservatives and adjuvants help keep vaccines safe and effective; extensive safety monitoring tracks any potential concerns over time.

Can vaccinated kids still get sick?

No vaccine is 100%, but vaccinated children are far less likely to become infected and, if they do, are much less likely to experience severe disease, hospitalization, or complications.

What an outbreak can look like in a community

- A traveler brings measles into a community where coverage has slipped.

- One contagious child attends school, daycare, or a public event before the rash appears.

- Multiple unvaccinated contacts are exposed; some infect infants at home or immunocompromised relatives.

- Public health teams trace contacts, exclude unvaccinated students, and set up post-exposure vaccination clinics.

- Hospitals see a surge of pediatric ER visits; some children are admitted with pneumonia or dehydration.

- Weeks later, more cases appear among those exposed before control measures took full effect.

This cycle is preventable. High vaccination coverage stops the first link in the chain from forging the second.

What parents and caregivers can do now

- Check your child’s vaccination record against your country’s recommended schedule.

- Ask your pediatrician about catch-up options if any doses were missed.

- Plan ahead for travel, college entry, and group activities that may require proof of vaccination.

- Use trusted sources for information and bring questions to your clinician.

- During outbreaks or exposures, follow public health guidance promptly, including post-exposure vaccination or medications when appropriate.

If you have a child with a complex medical history or immune condition, your clinician can tailor a plan to optimize protection—including timing, specific vaccine formulations, and strategies to reduce exposure during high-risk periods.

Key takeaways

- Unvaccinated children are at significantly higher risk for serious, sometimes life-threatening infections.

- The consequences extend beyond illness—affecting families, schools, and vulnerable community members.

- Vaccines are rigorously tested and continuously monitored; severe adverse events are rare.

- High community coverage prevents outbreaks and protects those who cannot be vaccinated.

Learn more from reliable sources

- CDC: Vaccines for Your Children

- CDC: Measles complications

- CDC: Pertussis complications

- CDC: What is polio?

- CDC: Haemophilus influenzae disease

- CDC: Chickenpox

- CDC: Rotavirus

- CDC: Flu and children

- WHO: Vaccines and immunization

- American Academy of Pediatrics: Immunizations

- NPR coverage: Vaccines

This article provides general information and is not a substitute for professional medical advice. For guidance specific to your child, consult your pediatrician or local health department.