Mind-Blowing Facts About the Marvels of the Microscopic World

The microscopic world is a universe within our own: teeming with alien architectures, nanoscopic machines, and physics that flips our everyday intuition. From bacteria that power electrical currents to molecular motors that spin like turbines, here are some of the most astonishing, reality-stretching facts hidden below the threshold of human sight.

1) Scales and numbers that bend the mind

- An E. coli bacterium is typically about 2 µm long—roughly 5,000 would span the width of a grain of table salt.

- Viruses are smaller still, commonly 20–300 nm across. A human hair (about 70,000 µm wide) is ~300,000 times wider than a 0.2 µm bacterium.

- Earth is a microbial planet: estimates suggest there are on the order of 1029–1031 microbes and perhaps ~1031 viruses globally—numbers so large they rival the count of stars in the observable universe.

- One human cell packs about 2 meters of DNA into a nucleus only ~6 µm across, coiled and looped with exquisite precision around proteins called histones.

- Ribosomes—the cell’s protein factories—are ~20–30 nm structures that can stitch together tens of amino acids per second, building the molecules of life at a pace rivaling assembly lines.

2) The tiniest machines rival our best engineering

- ATP synthase is a rotary molecular turbine about 10 nm wide that spins to make the energy currency of life (ATP). Your body turns over on the order of 1021 ATP molecules every second—powered by countless of these nanoscale rotors.

- The bacterial flagellar motor is a self-assembling rotary engine. Some species spin their flagella hundreds of times per second (reaching up to tens of thousands of rpm) and generate torques on the order of 1,000 pN·nm—remarkable for a device built from proteins.

- Cilia, hairlike structures on protists and cells in your airways, beat in coordinated waves. Their synchronization and metachronal rhythms allow single cells like Paramecium to sprint at dozens of body lengths per second in syrupy environments where normal swimming would fail.

- Virus capsids are geometric masterworks: icosahedral shells that self-assemble from identical protein parts into robust containers strong enough to withstand internal pressures rivaling a champagne bottle.

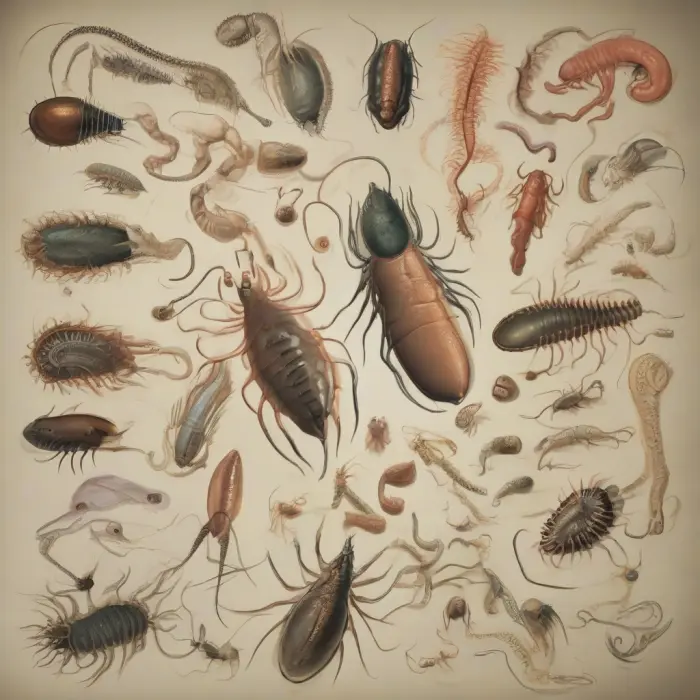

3) Survivors from the edge of the possible

- Tardigrades (water bears), often 0.1–1.2 mm long, can enter a cryptobiotic state in which their metabolism nearly stops. In this state they’ve survived intense radiation, extreme cold and heat, and even the vacuum of space before reviving with a drop of water.

- Deinococcus radiodurans can endure radiation doses thousands of times higher than would kill a human, thanks to superb DNA repair and stress-protective chemistry.

- Extremophilic archaea thrive where life seems impossible: near-boiling hot springs, hypersaline lakes, and ultra-acidic pools near pH 0.

- Bacterial endospores from genera like Bacillus can lie dormant for years to centuries, resisting desiccation, heat, and UV until conditions improve.

4) Architects and artists at the nanoscale

- Diatoms, single-celled algae, craft glass shells (frustules) from silica. Their nanostructured patterns manipulate light and are inspiring next-generation filters, sensors, and photonic devices.

- Radiolarians build intricate, spiky silica skeletons with mathematical elegance that rivals any human lattice design.

- Magnetotactic bacteria grow chains of magnetic crystals (magnetosomes) inside their cells, turning themselves into microscopic compass needles to navigate Earth’s magnetic field.

- Biofilms—microbial cities—are not just slime: they’re fortified communities encased in a matrix of secreted polymers with channels for nutrients and waste. In this state, microbes can be 10–1,000× more tolerant to antibiotics and stresses.

5) The planet’s hidden life-support system

- Oxygen from the oceans: Microscopic phytoplankton, including cyanobacteria and diatoms, produce roughly half of Earth’s oxygen—breath from beings you’ll never see.

- The Great Oxidation: Ancient cyanobacteria drove a planetary transformation over 2 billion years ago, gradually flooding the atmosphere with oxygen and enabling complex life.

- Nitrogen fixation: Specialized microbes “crack†atmospheric N2, converting it into forms life can use. The key enzyme, nitrogenase, is so energy-hungry it can consume ~16 ATP per molecule of N2 fixed.

- Electric microbes: Some bacteria (e.g., Geobacter, Shewanella, and “cable bacteriaâ€) move electrons across astonishing distances for their size, using protein nanowires or long multicellular filaments to plug into minerals like living cables.

6) Viruses: the most abundant biological entities

- By count, viruses likely outnumber cells on Earth by an order of magnitude. In the oceans, viral infections kill an estimated 20–40% of bacteria daily, recycling nutrients and shaping entire ecosystems.

- Giant viruses—like Mimivirus and Pandoravirus—blur the line between simple and complex, boasting genomes larger than some bacteria and elaborate replication strategies.

- Bacteriophages (viruses that infect bacteria) are genetic sculptors, driving microbial evolution and, increasingly, being explored as precision tools to treat antibiotic-resistant infections.

7) Microbes talk, trade, and remember

- Quorum sensing: Bacteria count themselves with chemical signals; when a “quorum†is reached, they switch behaviors collectively—turning on bioluminescence, building biofilms, or producing antibiotics.

- CRISPR is a microbial immune memory: bits of past viral invaders stored in DNA. When viruses attack again, microbes use this genetic mugshot to target and cut viral genomes. Humans adapted this trick into today’s gene-editing revolution.

- Horizontal gene transfer lets microbes share tools directly—like swapping USB drives. Genes jump via transformation (free DNA), transduction (via viruses), or conjugation (cell-to-cell bridges), spreading traits such as antibiotic resistance at astonishing speed.

8) Physics flips at small scales

- Low Reynolds number life: At micrometer scales, water feels like molasses. Inertia is negligible and viscosity rules. A swimmer that just opens-and-closes like a scallop goes nowhere; microbes use non-reversible strokes (e.g., rotating flagella, beating cilia) to move.

- Diffusion dominates: Over microns, molecules find targets quickly; over millimeters, diffusion becomes painfully slow. A protein can traverse a bacterium in milliseconds, but moving across a large cell or tissue may require active transport.

- Brownian motion: Thermal jostling constantly buffets small particles. Cells harness this “noise,†biasing random motion with molecular ratchets and cycles to do directed work.

- Molecular crowding: The cytoplasm is packed—tens to hundreds of grams of macromolecules per liter—so proteins navigate a bustling, gel-like metropolis, not a dilute soup.

9) The microbiome: your invisible organ

- Your body carries on the order of 1013 human cells and a comparable number of bacterial cells. The microbiome’s total mass is commonly estimated around a few hundred grams, varying by person and methods.

- Gut microbes help digest complex carbohydrates, synthesize vitamins, train the immune system, and may influence drug responses and aspects of metabolism.

- Disturbances to this ecosystem—diet shifts, antibiotics, infections—can ripple through health; researchers are exploring targeted probiotics, diet, and phage therapy as precision tools to nudge it back to balance.

10) Light, life, and luminescence

- Bioluminescent bacteria such as Vibrio fischeri glow when they reach high density via quorum sensing. The Hawaiian bobtail squid hosts these bacteria in a light organ to camouflage itself against moonlit waters.

- Photosynthetic nanomachinery: Pigment-protein complexes funnel solar energy with exquisite efficiency. In some systems, ultrafast energy transfer appears to exploit quantum-coherent effects at cryogenic temperatures—an area of active study.

11) Microscopic origins of modern technology

- Taq polymerase from the thermophile Thermus aquaticus made PCR practical, catalyzing the genomics era.

- Antibiotics from soil microbes (e.g., actinobacteria) revolutionized medicine; the race is on to discover new molecules from the vast “microbial dark matter†we still can’t easily culture.

- Microbial fuel cells and bioelectrochemical systems harness electron-shuttling microbes to clean wastewater and generate electricity.

12) Tools that reveal the unseen

- Fluorescence microscopy paints live cells with glowing tags to track molecules in motion.

- Super-resolution methods like STED, PALM, and STORM beat the diffraction limit, sharpening our view down to tens of nanometers.

- Electron microscopy maps structures at near-atomic resolution; cryo-EM flash-freezes delicate complexes to see them in their native conformations.

- Atomic force microscopy “feels†surfaces with a nanoscopic cantilever, letting us measure forces and topography molecule by molecule.

- Microfluidics sculpts flows in channels thinner than a hair, enabling lab-on-a-chip systems to culture, sort, and analyze cells with exquisite control.

Quick-hit mind-blowers

- A bacteriophage injects its DNA with pressures estimated at tens of atmospheres—like a loaded molecular spring.

- Cyanobacterial mats laid down layered rocks called stromatolites, some of the earliest visible fossils on Earth.

- A typical bacterium can double in as little as ~20 minutes under ideal conditions, outpacing the fastest factory lines ever built.

- Diatoms may contribute a significant share of global oxygen—some estimates place it near one-fifth—via their photosynthetic prowess.

- Microbes are master recyclers, breaking down oil spills, plastics like PET (e.g., Ideonella sakaiensis), and even rock, helping form soil.

Why it matters

The microscopic realm underpins everything: the air we breathe, the food we eat, the health we maintain, and the materials and medicines we invent. It is an engine of Earth’s biogeochemical cycles, a library of molecular blueprints, and a playground where physics becomes wonderfully weird. Understanding this world is not just about wonder—it’s about stewardship of the planet, advancement in technology and medicine, and recognizing that our lives are woven from threads too small to see but too important to ignore.