James Webb telescope spots a warped “Butterfly Star†shedding its chrysalis

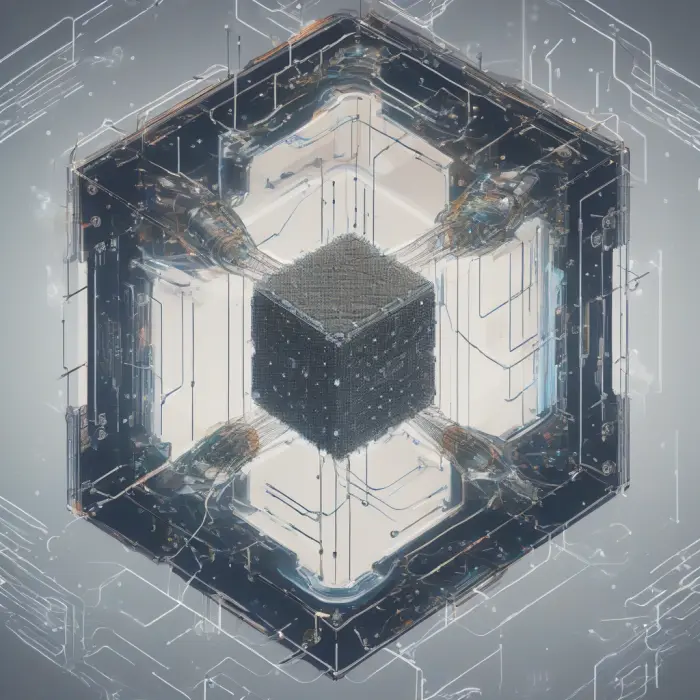

A new Webb portrait of a famously delicate, edge‑on young star system reveals a bent, shadow‑casting disk and a cocoon of dust in retreat — a fleeting stage between star birth and planetary construction.

At a glance

- Object: The “Butterfly Star,†a young, sun‑like protostar embedded in the Taurus star‑forming region.

- Distance: Roughly 450 light‑years away.

- Stage of evolution: Transitioning from a cocooned protostar to a young star with a protoplanetary disk.

- What Webb reveals: A subtly warped, edge‑on disk and an envelope that is thinning — evidence the system is “shedding its chrysalis.â€

- Why it matters: Warps can signal hidden companions or planet‑forming dynamics; shedding marks a brief, pivotal step toward planet‑building.

Meet the “Butterfly Starâ€

Astronomers have long nicknamed this object the “Butterfly Star†because, when seen in scattered light, the dusty birth environment splits into two luminous lobes — like wings — parted by a dark lane. That lane is the star’s protoplanetary disk viewed edge‑on: a flattened, rotating platter of gas and dust where planets may one day assemble. The glowing lobes are reflection cavities, hollowed out of the surrounding envelope by stellar winds and outflows.

Earlier telescopes captured the butterfly’s symmetry in visible and near‑infrared wavelengths, but the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) pushes deeper into the infrared, unveiling the heat and composition of dust grains and ices that are otherwise invisible. In Webb’s new portrait, the “wings†appear textured and layered, the dark midplane is not perfectly straight, and faint streamers of material trace the turbulent flow of gas and dust.

A warped disk with telltale shadows

One of Webb’s most striking clues is a gentle bend in the dark central lane and a mismatch in the angle of the bright lobes above and below it. These asymmetries betray a warp: the inner and outer parts of the disk are slightly misaligned, tilting in different directions. In an edge‑on system, such warps become visible because the disk casts shadows into the surrounding envelope; even a small tilt can shift the apparent “wing†shapes.

What can twist a young disk? Several culprits are plausible:

- A hidden companion — a small star or massive planet — whose gravity torques the inner disk.

- Magnetic misalignment between the protostar’s spin axis and the infalling envelope’s angular momentum.

- Uneven accretion as lumpy streams of gas rain onto the disk from different directions.

Whatever the cause, a warp changes where light and heat fall, potentially sculpting rings, gaps, and chemical zones that influence how and where planets grow.

Shedding the chrysalis

The “chrysalis†is the cold, dusty envelope that once cocooned the protostar. Webb’s sensitivity shows that this envelope is thinning. The reflection cavities look cleaner and more extended than in older images, and faint, filament‑like streamers around the lobes suggest material is being cleared by the star’s winds and jets. As the envelope dissipates, the system transitions from a heavily embedded protostar to a Class II young star dominated by its disk — prime time for planet formation.

This shedding is brief on cosmic timescales, lasting perhaps a few hundred thousand years. Catching it in the act offers a rare window into how raw, infalling material either settles into the disk or gets blown away, setting the budget of solids and ices available to build planets.

What Webb’s infrared eyes add

Webb observes in near‑ and mid‑infrared light, revealing:

- Warm dust and ices glowing at longer wavelengths, tracing the disk’s midplane and inner regions.

- Scattered starlight off fine dust grains in the cavities, highlighting their three‑dimensional shape.

- Molecular fingerprints from features such as silicates and hydrocarbons, which help map the chemistry of planet‑forming material.

In the composite image, longer wavelengths are typically mapped to reds and oranges, while shorter wavelengths appear as blues. This color coding separates hot, inner structures from colder, outer dust, and it accentuates the warp‑carved shadows that curve across the wings.

Why this “space photo of the week†matters

Beyond its beauty, the image captures three crucial processes at once: a protostar still accreting, a disk developing internal structure, and an envelope being expelled. Seeing all three together is a boon for models of star and planet formation. The warped disk points to dynamical complexity early on — perhaps even the fingerprints of nascent planets or a concealed stellar partner — while the receding cocoon signals that the clock for planet building has started in earnest.

What comes next

Follow‑up observations — for example, higher‑resolution imaging and spectroscopy across multiple wavelengths, and radio mapping of cold gas with facilities like ALMA — can:

- Pin down the warp’s geometry and search for a hidden companion.

- Measure accretion rates and outflow speeds to time the envelope’s dispersal.

- Map dust grain sizes and ice chemistry, key ingredients for planet formation.

Together, these data will show whether the Butterfly Star’s warped “wings†are a passing kink or a long‑lived feature shaping the architecture of a future planetary system.

Image notes and credits

This description is based on publicly released Webb imagery and common interpretations of edge‑on, cocooned protostars. Colors in the composite are representative, assigned to different infrared bands; they do not reflect true visual colors. Credit for the underlying observations belongs to the James Webb Space Telescope partners: NASA, ESA, and CSA, with image processing by the Space Telescope Science Institute and contributing teams.